(Image credit: stevepb)

Sometimes characteristics of products or services, or of those who sell them, immaterial as they are, can greatly influence our willingness to pay. Should they be any of our business?

500 years ago, on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther is said to have nailed his so-called 95 theses to the door of the chapel of the university where he was a professor of theology, in the German town of Wittenberg. In it he set out his fundamental objections to key elements of the Catholic doctrine and practices at the time. One of Luther’s main beefs with Rome was the widespread selling of indulgences, a kind of fast track ticket to heaven for sinners. In return for a generous donation to the Catholic Church they could redeem some of the time they would have to spend in Purgatory in the afterlife.

Luther’s objection was primarily theological: his conviction was that forgiveness for one’s sins required spiritual repentance, not cash transfers. But in a sense, he acted also as an early-day version of a consumer advocate, exposing indulgences as a product unfit for purpose. Ordinary people at the time had no way of verifying or challenging the claims of dodgy clergy, and so were effectively hoodwinked out of their money.

Unfixed values

Such practices are generally considered fraud nowadays. If you sell fake Rolex watches or Gucci bags, you risk prosecution. Misrepresenting material information in order to fool your customer into paying over the odds is generally illegal.

Early consumer champion with hammer

But that kind of fraud aside, knowing certain facts (or not knowing them) can significantly influence the price we are willing to pay for a good or a service. One of Richard Thaler’s classic thought experiments reveals the different price we are prepared for a beer on the beach (see ‘What’s the price?’). Standard economic theory says that we would establish the value of a beer based on how much we desire it, and irrespective of its provenance. But in practice, if we know the beer comes from a posh hotel we are willing to pay a good deal more than if we know it comes from a beach shack.

Let’s take this thought experiment a bit further. Imagine both you and your friend have read Thaler’s paper, and you agree two prices: a low one if she can buy the beer from a shack, and a high one if she needs to get it from a fancy hotel. She returns with the drinks, and you get your wallet to pay her. But how much? At that moment you don’t know where the beer came from, and none of its material features can make you any the wiser.

Your friend also happens to be a behavioural economist. To tease you, she refuses to tell you where she got the beer, and asks you to name your price. If it’s equal to or more than what she paid, you get the bottle, and if it’s less, she’ll drink it herself. Would you offer the true value of a beer to you, there and then, above which you’d rather stay thirsty? And would you feel miffed if that ends up being more than needed?

Not our business

This kind of reasoning, adjusting our willingness to pay to the underlying cost to the seller, doesn’t normally happen when we buy stuff from shops – a cup of coffee on the go, a loaf of bread, a winter coat…. Maybe that is because we assume that there is a reasonable mark-up, but usually we really don’t know. Perhaps the T-shirt for which we’re quite willing to pay the £20 shown on the price tag is bought in for just £2. If we knew, should that affect our willingness to pay?

Rationalists would of course say that is none of our business. As buyers, we should not concern ourselves with the details on the seller’s side prior to the transaction. No nonsense about beer from a shack or a fancy hotel, about mark-ups and profit margins. We should simply establish what a beer, a coffee, or a winter coat are worth to us, and use that to determine how much we’re prepared to pay. When we are thirsty we shouldn’t really be willing to pay less for a beer from one source than from another, any more than we should be offering less for a house that the seller inherited than for a house for which the seller made numerous mortgage repayments.

But it is it really irrational for us to incorporate the provenance of an item, or even the motives of the seller in our price deliberations? Isn’t it perfectly reasonable for someone to attribute value to the fact that their car used to belong to Steve Jobs, or to be inspired when they play on a guitar once owned and played by Beatle George Harrison… and pay literally over the odds for it? And isn’t it equally reasonable to take into account the negative emotions we might feel when we believe we are being overcharged by a seller only interested in a quick buck (and hence to reduce our willingness to pay)?

Our business

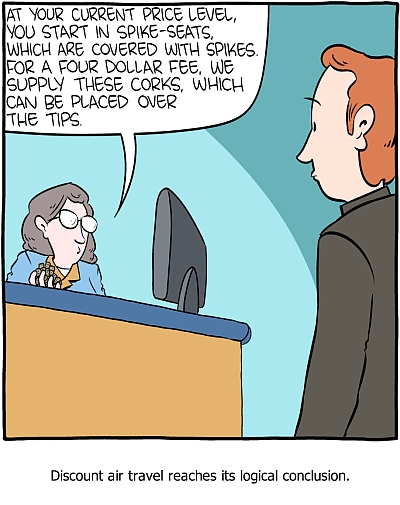

Perhaps it is our business after all. Just look at the practices of some el cheapo airlines. Zach Weinersmith captured the trend quite well in a cartoon last weekend:

Things may not be quite that extreme yet, but what about extra legroom seats? In the olden days, the seats next to the exits were actually a bit inconvenient: backrests that couldn’t recline, and awkward tray tables. But as airlines squeezed more seats into their planes, the safety obligation to leave enough space near the exits became an opportunity. These seats don’t cost them any more than the other seats, yet they charge more for them, because they can. Fast track boarding (not to heaven, though) is a similar case of economic rent: let ordinary people wait longer, and charge those who are in a hurry extra money, simply because you can.

Ouch, my knees! (source: StelaDi)

Ultimately it is our choice whether we want to make those immaterial aspects our business. Yet we should be careful not to actually become irrational in the process. If we are prepared to pay $7 for a beer from a fancy hotel, wouldn’t we be cutting of our nose to spite our face if we refused, out of principle, to buy a beer from a simple shack at the same price, if that was the only place selling it? If it really is worth £10 to us to travel in comfort, would it be rational to refuse to pay for an extra-legroom seat simply because we don’t want to give extra money to an evil airline?

There is no right answer to this: it depends on how much we value our principles. But that means we need to weigh them up against our thirst or our comfort, and not unconditionally let principles dominate.

The boundary between rational and irrational can be narrow and fuzzy.